Every School Board Everywhere Needs to See This Study.

This study is “a reminder that present enthusiasm for universal dissemination of short-term DBT-based group skills training within schools, specifically in adolescence, is ahead of the evidence.”

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) conducted a July survey that analyzed the amount of counseling, medication, or other forms of mental health therapy minors underwent in 2023.

According to the results, 8.3 million youth ages 12 to 17 received mental health care, which The Epoch Times noted “is equivalent to nearly one-third of the adolescents in the U.S. undergoing treatment for mental health issues.”

This generation of kids — who would benefit from less therapy, not more — is receiving more mental health treatment than any generation before it.

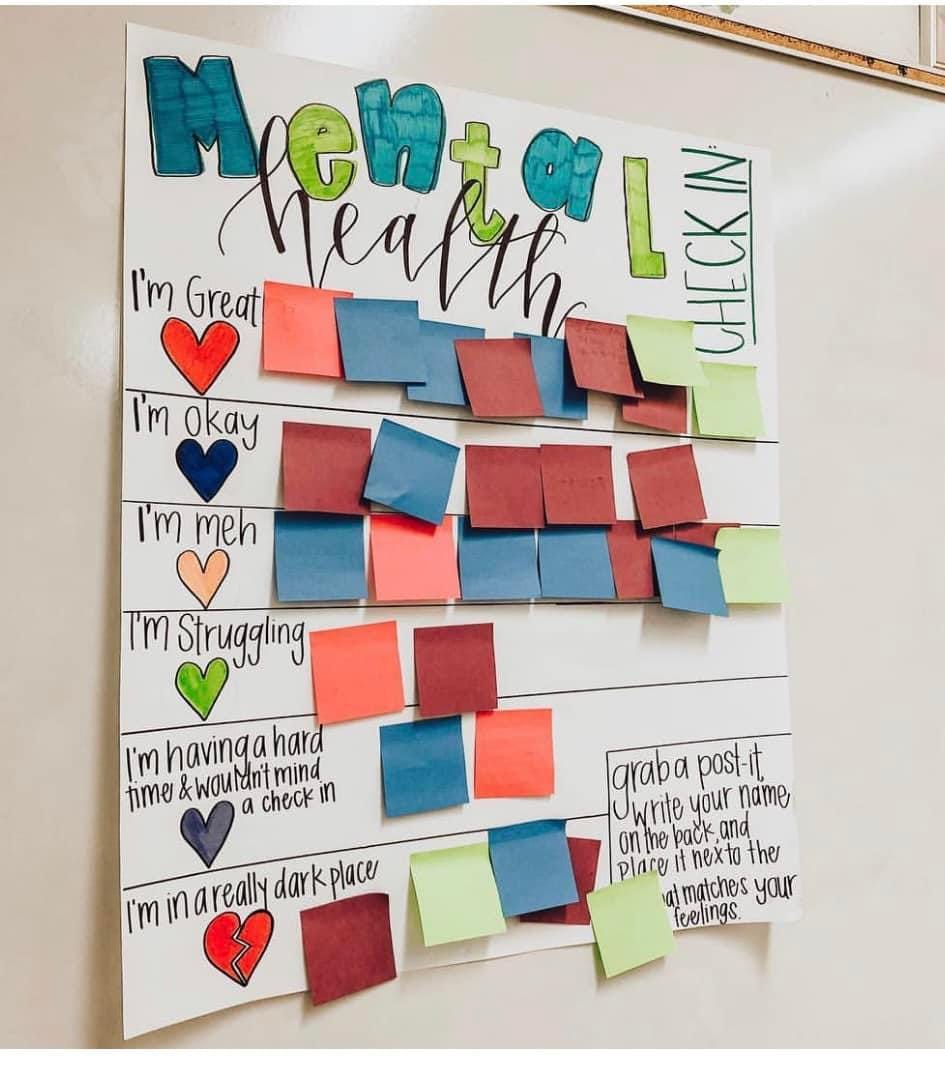

In K12 schools, kids are receiving mental health surveys, social emotional learning (SEL) lessons, talk therapy, and other interventions — and this isn’t limited to kids who demonstrate a need for such things.

As author Abigail Shrier says, the mental health focus in schools “has gone airborne.” EVERY student is subject to daily check-ins, surveys, “mindfulness” practices, SEL instruction, or class group therapy sessions.

Kids who misbehave in class are no longer sent to the principal’s office. Now, they’re sent to a school counselor for a mental time-out and a discussion about feelings.

Accordingly, the Biden administration has made hundreds of millions of federal dollars available to school districts in 2024 in order to expand school-based behavioral healthcare on an unprecedented scale.

In some school districts, unlicensed behavioral health workers are setting up shop in schools, ready to influence children without parental knowledge or consent.

How many “mental health professionals” has your district hired for the 2024-25 school year, or is planning to hire? Ask your board if these personnel are required to be licensed by a professional board and if they will receive regulatory oversight.

Many novice school counselors and social workers are certified by state departments of education, but are not licensed to practice by a regulatory board. They work with children in schools with ZERO scope of practice limitations and NO FEAR of malpractice lawsuits.

The pervasive therapeutic education model in our nation’s schools actively promotes the infantilizing, feelings-focused, therapeutic culture which seeks to affect every aspect of today’s kids’ lives.

What can parents do?

Show your school board, superintendent, and school principal this study: “Investigating the efficacy of a Dialectical behaviour therapy-based universal intervention on adolescent social and emotional well-being outcomes,” authored by Lauren J. Harvey, Fiona A. White, Caroline Hunt, and Maree Abbott.

This 2023 study shows that broad, universally applied mental health practices in schools actually worsen kids’ mental health.

In conducting the study, the researchers evaluated a program for 8th & 9th grade students called WISE Teens.

The WISE Teens program utilizes Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT).

“Dialectical” means combining opposite ideas. It’s talk therapy with a focus on helping people both accept their reality and at the same time change behaviors or thought patterns which are proving unhelpful or harmful to them.

Sounds great, right? Well…

It turns out, regular mental health sessions in school were ineffective in aiding 8th & 9th grade students in improving their emotional well-being and interpersonal relationships.

In fact, the group of kids that underwent this program experienced deteriorating mental health indicators immediately following the interventions, as opposed to the control group.

For many children, trouble starts when adolescence hits. Torrential hormonal and other physiological changes can manifest in what appear to be disorders or poor mental health.

Many researchers’ work is focused on developing interventions aimed at preventing mental disorders in adolescence (ages approximately 12 to 25) and helping adolescents maintain mental health. At the same time, access to mental health services reaches its lowest point during adolescence, and adolescents are often not willing to spend time interacting with mental health service providers.

Because of this, many see schools as an ideal setting for implementing preventative measures. People just assume more attention to kids’ mental health during the school day with things like social emotional learning curricula and regular check-ins with a school counselor will benefit them, despite the data that indicates otherwise.

Mental health interventions in schools are generally designed as universal procedures, targeting all students. They focus more on general risk factors for mental illnesses rather than specific mental health symptoms.

A common goal of these interventions is to help students enhance their emotion regulation skills. However, the effectiveness of these universal interventions in school settings has yielded mixed results, with some studies, such as the one featured in this post, even indicating adverse effects.

As explained above, study author Lauren J. Harvey and her team evaluated the effectiveness of the universal school-based intervention WISE Teens, which, as mentioned, utilizes Dialectical Behavior Therapy.

The researchers conducted a quasi-experimental study for this purpose.

The study involved 1,071 students in the 8th and 9th grades from two independent and two government high schools in the Sydney metropolitan area, Australia. The average age of the participants was 13-14 years, with 51% being male.

In each school, 8th-grade students were assigned to one study group, and 9th-grade students to another. Schools decided which group would receive the intervention and which would serve as the control group.

The intervention program, WISE Teens, included eight weekly sessions adapted from the DBT STEPS-A curriculum, a Dialectical Behavior Therapy program tailored for adolescents. It combines skills training and psychoeducation to address emotional dysregulation, interpersonal issues, and self-destructive behaviors.

Each session lasted 50-60 minutes and covered modules on mindfulness, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness. While the intervention group participated in this program, the control group continued with their regular classes.

The study’s authors conducted assessments at three points: before the intervention, immediately afterward, and six months later.

Participants completed a comprehensive set of assessments measuring emotional and behavioral characteristics, resilience, emotion regulation difficulties, stress, depression and anxiety symptoms, emotional awareness, quality of life, and beliefs about emotions.

Additionally, those in the intervention group kept weekly diary cards, noting their practice of mindfulness techniques, and, six months post-intervention, they reported the frequency of practicing skills learned in WISE Teens.

Here’s what happened: Contrary to expectations, students who completed the WISE Teens program reported increased overall difficulties and worsened relationships with parents. Their depression and anxiety symptoms also increased after the intervention.

Compared to the control group, participants in WISE Teens exhibited heightened emotion dysregulation, reduced emotional awareness, and decreased quality of life. No change was observed in academic resilience.

Notably, 13% of WISE Teens participants experienced a significant worsening in depression symptoms post-intervention, compared to 7% in the control group.

From the study: “When examining the secondary emotional well-being outcomes immediately post-intervention, again contrary to predictions, a similar pattern in findings was observed. Pairwise comparisons applying Bonferroni corrections indicated that participants in the ’WISE Teens’ condition reported significant increases in depression (t(2598.99) = −4.65, p < .001; d = −0.22; 95% CI = −0.35, −0.08) and anxiety (t(2590.65) = −5.89, p < .001; d = −0.28; 95% CI = −0.41, −0.14).”

It’s worth noting that other studies have also found that mental health intervention programs employed in school-based settings, particularly group-delivery formats, produce iatrogenic effects.

Iatrogenicity is when the treatment actually makes the problem worse, a somewhat common corollary trait of talk therapy. Here’s one such study that shows this correlation.

Back to our study.

In the assessment 6 months after the intervention, most of the differences between the WISE Teens and the control group disappeared. However, the WISE teens group still reported poorer relationships with parents compared to the control group.

This is a feature of such programs, not a bug. The impact of school-based interventions such as this on the parent-child relationship is often negative.

Listen to Abigail Shrier, author of Bad Therapy, talk about this aspect:

The study authors concluded, “Significantly poorer outcomes were observed immediately following participation in the 8-week DBT-based universal intervention (‘WISE Teens’) compared with curriculum-as-per-usual. Of concern, the current study is the first to show in the universal intervention literature that both in the immediate and short-term (6-months) such a program may foster significantly poorer quality parent-child relationships relative to curriculum-as-per-usual.”

And the authors final thoughts: “There is great enthusiasm for applications of DBT across contexts. However, the current study is a reminder that present enthusiasm for universal dissemination of short-term DBT-based group skills training within schools, specifically in early adolescence, is ahead of the research evidence.”

#KIDSFIRST

Article: Study highlights potential adverse effects of universal school-based mental health programs